Random Numbers:

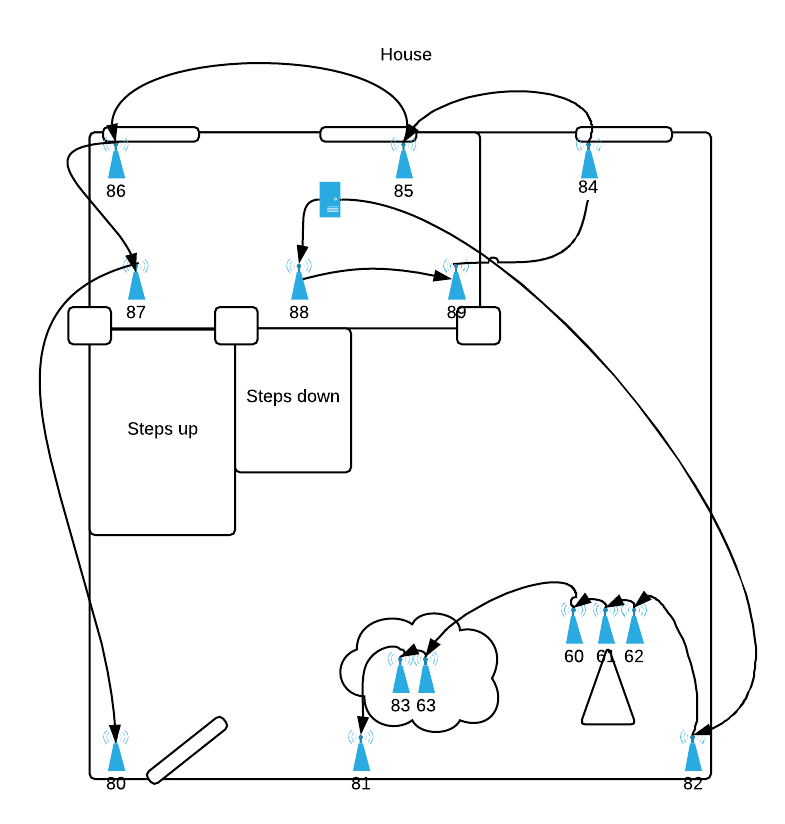

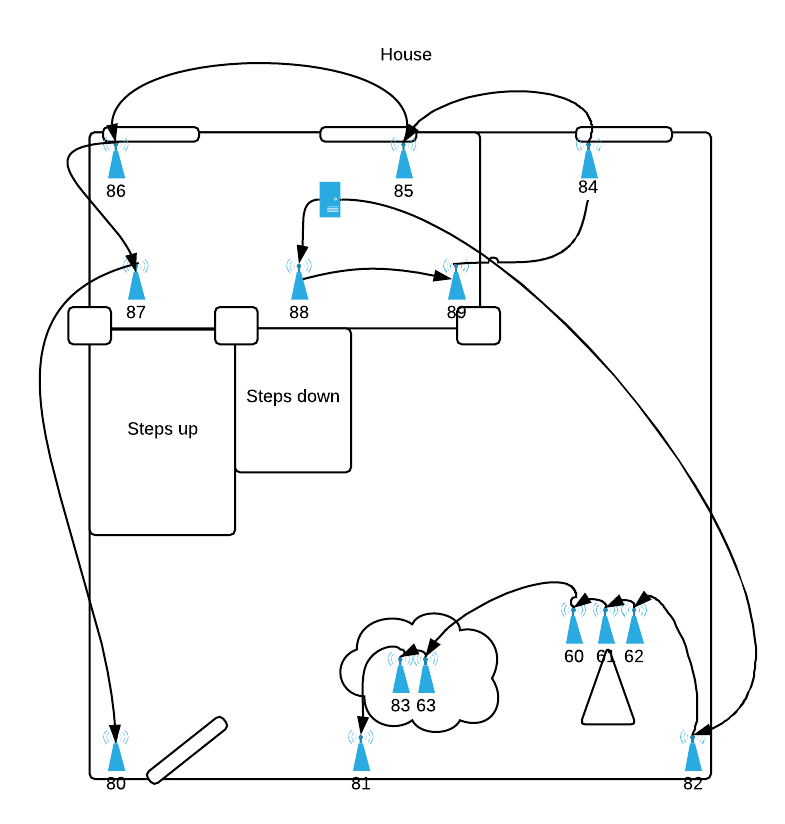

- Total Strands: 98, 4 each Red/Blue/Green/White, 2 Meteor

- LEDs: 9,888

- Controllers: 1x Pi Zero, 1x RS-485 Repeater, 14 RS-485 Controllers

Coding, Beer, whatever else

Random Numbers:

This describes our assignment of responsibility between Foreman and Puppet. For an overview, please see Part I .

Our original configuration relied primarily on Foreman to define services, required classes and their supply configuration parameters. This left puppet to solely provide a mix of modules (ie autofs, etc) and profile-like classes which would be glued together by foreman at the Host Group level. When we started down the path we were on Ubuntu 12.04 (~2013) and running Foreman 1.2 or 1.3. Config Groups were not yet and option and the UI tended to force most configuration overrides to occur when configuring classes.

At first, this configuration worked well, however it soon became unwieldy list of classes (400+) that were listed in foreman and the assignment per host started to get quite cluttered. For example the configuration of a research VM running our standard R setup was three Host Groups deep, and had 27 different classes whose configuration was keyed off a mix of host group and domain. Managing this, and determining what got applied where and ensuring configuration changes didn’t have unintended side effects became a burden. Additionally, adding new classes meant weeding through the 400+ included to find what you needed. In addition, as the groupings and configuration were all in Foreman, creating a development environment was a fairly manual process of recreating the host groups and applying all the configuration overrides.

The configuration we were performing on classes fell into two categories, service-based config where items like db names and who has access to a service would vary depending on the service and the static configs for items like overall domain configuration, core apt repo’s that would almost never vary once setup.

In hindsight, setting up ignored_environments.yml would have saved us some heartache and led to a cleaner class list. It wouldn’t have led to clarity on the filesystem of easily knowing which modules were top level modules (ie, foreman directly applies) vs modules that were installed to fulfil dependencies.

In our new configuration, we realized that we needed to draw a line between where configuration and class application should occur. This can be a bit tricky as there is substantial overlap between what foreman provides and what puppet provides.

In deciding whether foreman or puppet should be responsible for a particular item we decided to use the following guidelines:

We started by looking at the Roles and Profiles pattern in Puppet and seeing how we could adapt this to Foreman. The first mapping that was pretty obvious is that a Foreman config group is a puppet role. Both do not allow parameters and both are supposed to be composed only of classes. So config groups or roles? In order to allow an admin logged into foreman to see what services are running on a host, we decided to use Foreman config groups in favor of Puppet roles.

The next step was to reduce the surface area between foreman and puppet to clearly defined lines of control. Previously we had directly included any puppet module in a config group and applied configuration on foreman via smart parameters. This time, following the profile pattern, we define one profile per service and expose only these profiles to foreman by filter in ignored_environments.yml.

:filters:

- !ruby/regexp '/^(?!role|profile).*$/'

These profiles have configurable service configuration exposed to foreman as parameters. Where possible, sane defaults for our environments are provided if we decide to even expose a parameter rather than configure it in the profile class. These profiles are combined using config groups and applied to Host Groups. The diagram below shows roughly what this looks like:

What about Hiera?

We considered using Hiera to manage global configuration options, but after mocking up some workflows and seeing how little data we would actually have in it vs foreman decided to just put those configuration values in the various profiles. A second reason for not using Heira was to reduce the number of places to look for configuration. While not too bad, using Hiera would have let to a second code repo which would have required careful synchronization with the main puppet code repo. We may revisit this in the future as the need arises.

Over the past four years we’ve deployed a puppet/foreman environment to support Ubuntu 12.04 and 14.04 for our research and production Linux systems. As 12 is approaching end of life and there are no longer Foreman updates available we decided it was a good time to revisit our overall puppet/foreman integration. Over the years it had slowly grown to include a bit of cruft and needed a good haircut. In addition, during the past four years, Foreman had added additional features which made it a good time revisit how the two communicate and where the hand-off in responsibility lie. So with that introduction, the environment we deployed had the following goals and challenges in mind:

Skipping ahead to the end, our final Foreman environment consists of the following. We ended up creating a separate dev and production environment which were 100% independent, yet mirrors of each other. We developed a workflow for allowing each developer to have their own environment and setup a clean separation between this development environment and the testing environment/production environment. This allows the production side to quickly test and apply security and other upstream updates without impacting longer term development efforts.

Foreman and Puppet

Git and Environments

In parts two and three, I’ll cover a bit more about the motivation and detail behind this setup.

Some additional reading:

Looks like the password phishers are finally starting to learn proper grammar and piece together something kinda convincing. Here’s a breakdown on one that I had reported to me over the UMD holiday break. It’s notable for a few reasons:

Here’s the actual email received from these guys. A few things they got correct:

The login they created for this account is a pretty convincing copy of UMD’s actual CAS login page. The top/forged one uses graphics from UMD. Looking at the source, the login form has been modified to send the response to save.php.

If you go to the root domain, edu-lib.ml, there are a half a dozen other universities listed with what I’m assuming are forged copies of their login pages. Entering any username and password into the password field results in a message saying your services have been activated and a link back to UMD’s library main page.

Overall, I’d have to give this one a B+ for the realness factor. Sadly, it probably picked up quite a few accounts given timing, etc.

Quick hack to have a bounded slider in Konva